Why does one fast?

The obvious answers to me are most likely for spiritual or health reasons, and, should the need arise, for political and judicial reasons as well.

But who knows really — it’s such a strange thing to do if you think about it.

Back in the Nineties, which some Dennis Hopper character in some forgotten movie referred to as the Sixties standing on your head, I was a fasting vegan. That’s right, I was vegan not just before it was cool, but even before just about anyone had even heard of the word, and certainly before most of today’s nouveau hipster dreadlocked vegans were even born. I won’t attempt to analyze their motivations for become a vegan, but mine began in my desperate pursuit to quit smoking.

Long story short, one day out at sea — yes, I was a vegan sailor boy of all things — I stumbled upon an Anthony Robbins book in the ship’s library and from it I discovered things that took me on a long strange dietary journey beginning with food combining (not mixing proteins and carbohydrates), to your basic vegetarianism, to the Diamond’s Fit for Life with their whole body hygiene lifestyle maintenance system, which included veganism and eating according to the body’s cycles, to Deepak Chopra’s Perfect Health, to Arnold Ehret’s Mucusless Diet, to Mark Mathew Braunstein’s Radical Vegetarianism, which, if I remember correctly, is the book that led me finally to fasting.

Ah, the Nineties… what a decade.

The good news is I haven’t smoked since…

However, while I remained a vegan for most of the decade, the fasting* didn’t really stick with me.

It is a tough gig, this fasting. One learns very quickly how weak the flesh is and how strong mentally one must be to overcome this weakness.

Just ask perhaps one of our most renowned fasters throughout history – Jesus.

God only knows how he was able to not only fast for forty days, but to do so while also fighting off the devil’s relentless temptations.

Talk about mental toughness.

I recall reading, in which book I can’t recall, probably Radical Vegetarianism, that when fasting, the liver creates its own glucose and other enzymes to compensate for the lack of nutrients. One of these enzymes supposedly has the same effect on the brain as does LSD.

Could explain why there are so many trippy fasting ascetics throughout the ages…

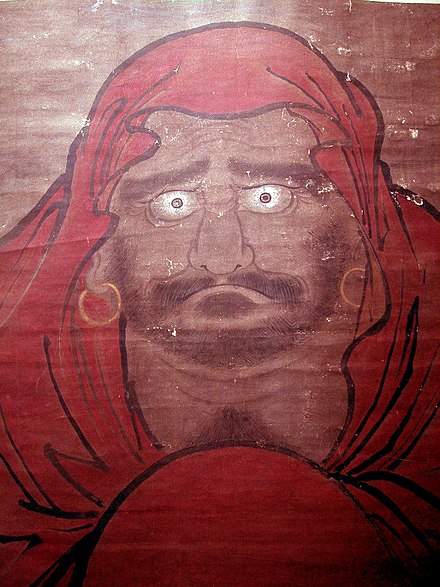

Like Bodhidharma sitting in a cave in silence, abstaining from just about everything, which I imagine would also include food, and staring at a wall for nine years, I guess in an effort to convince/influence his growing flock of Chinese followers to follow him down his particular path to enlightenment.

Yeah, I don’t know but whatever the reason was for him to stare at that wall for so long, he was textbook trippy fasting ascetic if you ask me.

I don’t know about you, but to me if in your effort/desire to achieve enlightenment you find yourself sitting in a cave and staring at a wall for nine years, then, well, it seems to me that your efforts/desire to shed yourself of desire has transcended beyond desire into a weird neurotic fetish, spiritually speaking of course.

Anyway… I was looking through my old journals from the Nineties and I came upon some notes I took from an essay by the late Shin’ichi Hisamatsu titled “The Characteristics of Oriental Nothingness“** and I found a passage from the essay that must have struck me then as I copied it verbatim, and which I will share with you now as it seems to apply to our current trippy discussion:

“The Mind in its dimensions is broad and great, like empty-space. It has no sides or limits; it is neither square nor round, neither large nor small. It is neither blue, yellow, red, nor white; it has neither upper nor lower; it is neither long nor short. It knows neither anger nor pleasure, neither right nor wrong, neither good nor evil. It is without beginning and without end. But good friends, do not, hearing me speak of emptiness, become attached to emptiness.”

Seems to me our good friend Bodhidharma kind of got attached to emptiness more than just a little bit, no?

Now, I don’t know if that wide-eyed monk (I’ve read somewhere that he cut his eyelids off so he could meditate without the interruption of blinking or sleep) became so attached to emptiness as embodied by the wall in that cave because he was tripping like a hippie at Woodstock due to the LSD-like enzymes polluting his head from an overabundance of fasting, or if he just had a bad case of misanthropy or what, but his kind of ascetism kind of reminds me of that of the protagonist in Kafka’s “A Hunger Artist.”

Now this ascetic dude literally turned fasting into an art form.

That is, if you can call sitting on straw in a cage all day where the only thing you do is not eat art.

It’s one way to become a star, I guess.

I guess another way is for absolutely no reason other than you’ve somehow managed to convince a million others to follow you on the latest social media flavor of the day for no other reason than because a million others follow you…

Whatever.

Influence is influence I guess, no matter if it comes from your ability to cure cancer or your ability to manipulate the social media app into putting cute dog ears on a cute photo of you.

But by the time we come upon the Hunger Artist in the story, his influence is on the wane and we find, regardless what his reasons were for becoming a performing ascetic, be they for spiritual reasons or not — my guess is not but who knows, right? — this ascetic dude is desperate to keep performing.

Because by now, it’s all he knows.

I mean, if all you do is sit on straw in a cage (or sit in a cave in front of a wall) doing nothing but not eating day after day, year after year, sooner or later that shorthand skill you picked up as a side-hustle during college is going turn stale and leave you with no other options but to continue sitting on straw in a cage doing nothing but not eating.

And, where once he was performing maybe because he felt what he was doing was bringing a certain joy and enlightenment to the crowds he used to draw, now it’s he either performs or he…

Well, I don’t want to spoil the story for you if you haven’t yet had the pleasure to read it.

But, if you know anything about Kafka, then you can probably imagine what would happen to such a strange, desperate character of his at the end of such a strange, desperate tale.

At least he, the Hunger Artist, is not the poor strange soul at the end of In the Penal Colony.

But he suffers nonetheless, our poor ascetic known as the Hunger Artist, who, alas, I presume is just one more soul Kafka leverages to illustrate the sense of alienation he felt from a society wholly incomprehensible to him…

And he to it.

So, he — take your choice as to who the he may be here, the Hunger Artist, Gregor Samsa, Joseph K., K., Kafka himself, you? — found for himself a life where he could separate himself from others, and be protected from them sitting safely behind the steel bars of his cage, and where he could even find a sense of glory from them.

And all he had to do was refrain from what it was that is common to all, including himself, from whom he wished to separate himself from.

In other words, all he had to do was fast.

And it was something he did very well, right up to the end.

*While I never stuck with long-term fasting, I do adhere to intermittent fasting, trying to go at least 16 hours a day without food.

**This essay was published in 1946 and the language is a bit dated so don’t get all bent out of shape at me for it… please.